Question: What is the Dunning-Kruger effect?

So one answer is that it is a phenomenon in the human brain regarding our ability to retain information as well as how our brain encourages us to learn. Learning simply feels good. Whether that reinforcement comes from a teacher or parent encouraging us, or if it is just the personal satisfaction of something becoming easier and easier, our brain is wired to reward the feeling of understanding the patterns of the world around us and moving through them more effortlessly.

Now, before we get further into this definition, let me ask you two questions. First off, have you ever known that you are experienced, competent, confident and prepared for a job but still felt a small voice in your head telling you that you should actually just step to the side for someone who knows more? Or, on the other end of the scale, have you ever worked with someone who clearly had no idea which was the backend and which was the front, but nevertheless they spoke the loudest, and their confidence carried them through failure after failure?

Me too.

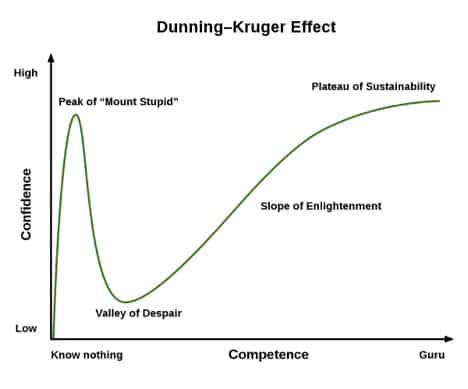

Alright: Dunning-Kruger time. Below is a graph of the “Dunning-Kruger Effect,” and a graph may sound like an insane way to depict a psychological phenomenon, but bear with me (and our friends at the Wikipedia Commons).

So, from bottom to top (your Y axis), we have a person’s confidence in a topic—the farther toward the top you are, the more confident you are that you absolutely have the goods. From left to right, we have your experience and “actual skill” at the topic at hand. So, if our “skill” is pitching a baseball, then the farther up you are means the more psychologically confident you are in yourself, and the farther to the right you are means the closer you are to making it into the hall of fame. Now, here is where things get interesting: track the line in the middle which represents an “average” person taking on a new task. Notice that for this generalized mind, the line of their confidence skyrocketsearly on, dips into what our graph calls the “Valley of Despair” and then curves back up until evening out at the original feeling of self-satisfaction. Think about this for a bit.

First, do you have children, younger siblings, or even nieces or nephews? My brother is eleven years younger than me, so from ages 15 to 20 I remember constantly offering my brother help like “As a right-handed batter, you want your right hand above your left on the baseball bat” or “Yeah, she didn’t think you were flirting because you kept talking about yourself.” In any case, the answer tended to be “I KNOW THAT!!” even as they swap their left and right hands around to follow your instructions. Second, have you ever picked up a new talent—golf, singing, running, even just a new specialization at work—and been going for a few weeks only to realize that there are actual “pros” out there who “could” look down on you some day? Like you are going to your local driving range and both Tiger Woods and Phil Mickelson pull up on a cart to laugh at your backswing? Whether it is #1, #2 or both, let’s go back to the chart.

The proposition of the Dunning-Kruger effect is this: because our brain rewards us for learning, it is incredibly easy to get swept away when developing a skill and tell ourselves that nobody in the history of humanity has picked up pottery or calligraphy as quickly as ourself; therefore, we are bound to imminently pen our own signature into history. Alternatively, what the Dunning-Kruger effect says is that this well of instant satisfaction actually runs out pretty quickly; once you feel the immediate surge of reward taper off and you emerge into the intermediate phase of any talent or task, then your brain starts operating in a completely new way. Why would I ever touch my cleats against a soccer ball when ESPN seems awash in freaks who can sprint for ninety minutes and lace the ball perfectly to a teammate each time they swing their magic wand of a foot?

To be short, everything behind either of those scenarios is because we can be incredibly easy or hard on ourselves, but what’s important is that we do this for a reason. And by understanding that reason, we can become wiser and stronger.

To return to the concept of the child who retorts “I already know that” to your most direct and needed advice, think of such unearned confidence as the product of immaturity. The Dunning-Kruger model is not saying you are an inescapable slave to this product of your own dopamine; instead, think of it as a trap. Don’t let the rush of learning a new skill distract you from the discipline and time it will take to become fully immersed. Alternatively, and no less importantly, do not let the initial or secondary or tertiary hangup in learning become a massive setback. Here, the concept of “Imposter Syndrome” isn’t just a personal experience of your own as you grow, but instead something to be anticipated and therefore easier to overcome.

As a final note, again focus on the graph as a trend rather than a destiny, a biological trap or a kind of psychological tax to inevitably be evened up. What Dunning and Kruger are not saying is that we cannot escape this; they are advising us to be more metacognitive (that is, to think about our thinking). Personally, I believe that part of growth and maturation is the refereeing of our own personal line on the graph between confidence and skill. Would not the ideal path be one of a steady line of growth? Pick your own degree of progress from 1 to 89 degrees, but could it not be possible to try to correlate and align your own growth as well as your satisfaction with yourself? Perhaps that is too fantastic for every scenario, but look back at that graph and imagine it with more ups-and-downs, yet they each deviate more closely to a central line. Less of a rise and crash, it consistently averages its way up while being honest about each the good and hard days. Wouldn’t that be easier? That crash into the “Valley of Despair,” as this graph calls it, is where we quit – where we blush and tell ourselves we aren’t that good. However, a regular reality check or even a bruise here or there is much more easy to withstand than complete disillusionment with yourself.

To close, if you are losing confidence in yourself, confront that feeling—perhaps it comes from good judgment (obviously possible) to take into account, or maybe it’s your brain realizing that moving from tee-ball to pitching is hard because it’s supposed to be. There are breakthroughs to come. Alternatively, if you have that unignorable mosquito-bite feeling from another person because their unshakable confidence makes you start to believe that they really are that and a bag of chips, try to trust some of your own instincts and see their false confidence.

Slice of LIFE is an invitation to and extension of everything happening at Life U. Whether you are a current student, a potential freshman or a proud alumni, Slice of LIFE can help keep you connected to your academic community. Know of a compelling Life U story to be shared, such as a riveting project, innovative group or something similar? Let us know by emailing Marketing@life.edu.

Social Media